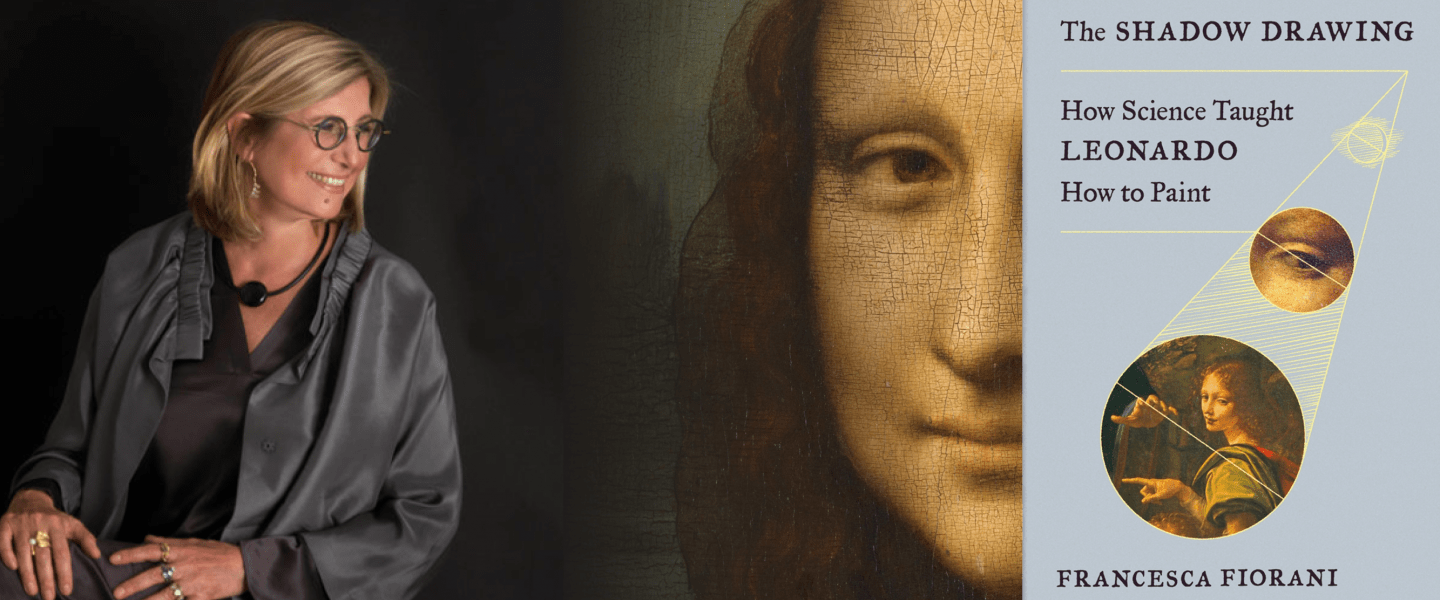

It's difficult to imagine how there could be anything new to reveal about Leonardo da Vinci and his art, but that's exactly what Francesca Fiorani has accomplished. A professor of art history with the College of Arts & Sciences, Fiorani believes that the prevalent idea of da Vinci as a painter who abandoned art for science is a mistake. In her latest book The Shadow Drawing: How Science Taught Leonardo How to Paint, Fiorani explores the idea that the marriage of art and science was fundamental to da Vinci's genius.

In an article published by UVA Today on February 26, 2021, Fiorani spoke about her book that The New York Times said, "Reorients our perspective, distills a life and brings it into focus," and she discussed some of the biggest misconceptions about the original Renaissance man.

Reading an article about a famous computer-generated scene in the Hollywood film “The Matrix Reloaded,” University of Virginia art history professor Francesca Fiorani couldn’t stop thinking about Leonardo da Vinci.

The article focused on a digitally created fight scene in the sci-fi film in which Keanu Reeves, as Neo, dodges a barrage of bullets. The artists and animators behind the 2003 film said the most difficult part of such scenes was realistically recreating the shadows on people’s faces in different, fast-changing positions.

“That is the exact problem Leonardo da Vinci worked to solve, though of course he worked with brushes and pigments instead of pixels,” Fiorani said.

Fiorani is UVA’s resident expert on da Vinci. She writes and teaches about the intersection of art, science and technology in the Renaissance, and led a project digitizing da Vinci’s “Treatise on Painting,” a tool that scholars all over the world now access and use. Her new book, “The Shadow Drawing: How Science Taught Leonardo How to Paint,” has garnered a lot of attention for its insistence that the conception of da Vinci as an artist who switched his focus from art to science is at best simplistic, and at worst simply wrong.

Francesca Fiorani has studied da Vinci for years, and led a project digitizing his “Treatise on Painting.” (Image courtesy Francesca Fiorani)

“There is this idea that Leonardo trained as an artist and then suddenly became a scientist later in life – or, to be more precise, a ‘natural philosopher’ as scientists were called then. Something in that view of the man – him as this ultimate ‘Renaissance man’ – did not convince me and did not square with the evidence I was gleaning from his early works,” Fiorani said. “Leonardo did not become a scientist at all; he was one all along.”

We spoke to Fiorani after her book’s publication and asked her to share a few things she wants us to know about da Vinci.

His interest in science is the foundation of his art career.

In da Vinci’s early works, Fiorani sees signs of the scientist he would later be known as.

“These are exceptionally beautiful and striking works that were not like anything else being painted at the time,” she said. “For him the ultimate expression of knowledge, even scientific knowledge, was painting. If he could paint something, it meant he understood it.”

That is why, Fiorani said, da Vinci became especially known for his mastery of subjects that are both deceptively simple and difficult to capture on paper – a fleeting expression or mood, a subtle smile, the interplay of light and shadow at a given moment.

“One of the most difficult things to understand is the human mind and the way people feel; therefore, for Leonardo, that was one of the most difficult things to paint,” Fiorani said. “His subjects rarely have dramatic expressions – they are not shouting or pulling their hair. Instead, what we have are subtle, delicate smiles, a slight turn of the face, or of the body. His goal was to precisely capture those minute shifts of the human mind – not the dramatic feelings, but the almost unconscious moods and changes of mood we all experience.”

Da Vinci was likely influenced by Arab philosopher Alhazen’s “Book of Optics.”

In her book, Fiorani draws connections between da Vinci and an 11th-century manuscript, “Book of Optics,” by Abu Ali al-Hasan Ibn al-Haytham, known in the West at the time as Alhazen.

“The Book of Optics really considered optics as a form of philosophy, not just a study of how we see – though it was also that – but a study of how we learn about the world through the senses, especially the sense of sight, which for Alhazen, and for Leonardo too, gives us the most accurate knowledge of the world,” Fiorani said. “What do we do with sensory experience and how do we transform sensory experience of the world into knowledge of the world?”

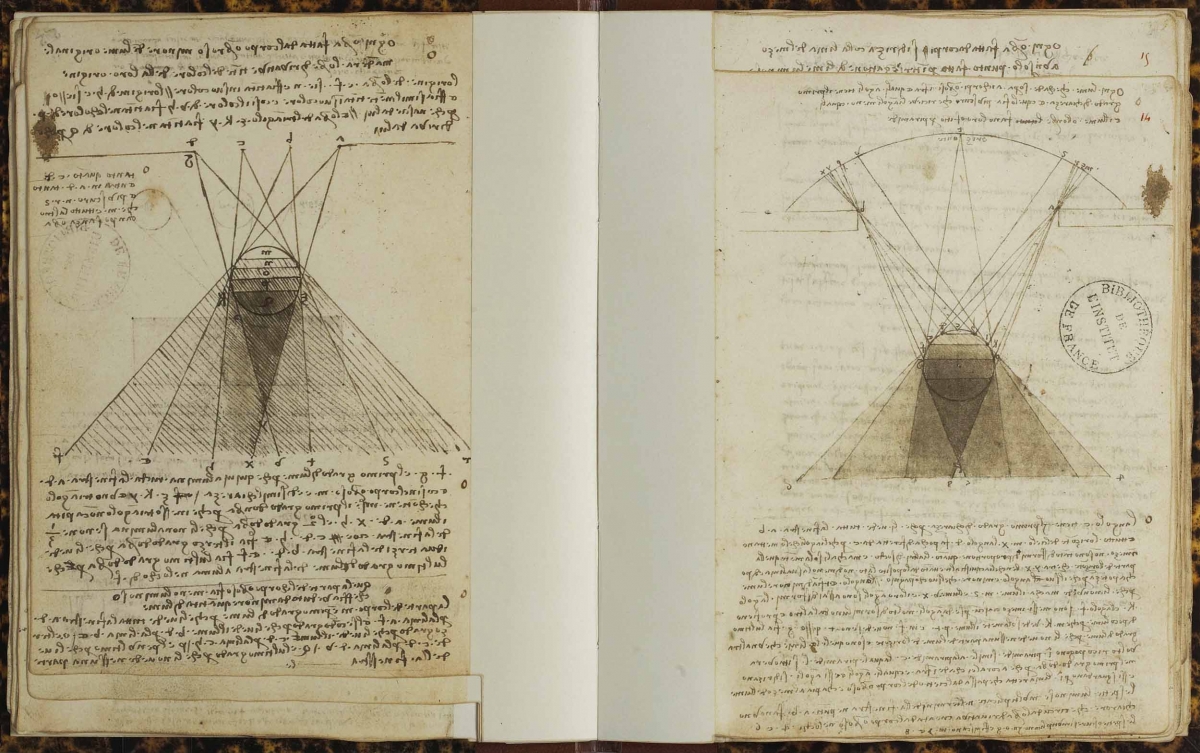

Shadow Drawings from Leonardo da Vinci’s notebook, known as Manuscript A and kept at the Bibliotheque de l’Institute in Paris. (Image courtesy Francesca Fiorani)

Though there is no direct evidence that da Vinci read the book, Fiorani lays out compelling circumstantial evidence in her book. Originally written in Arabic, the Book of Optics was translated into Italian sometime in the 14th century, and circulated in artistic circles in Italy as da Vinci was starting out his career.

“It is pretty likely that he read the book, because we know he was present in Florence at this time, and we know of artists with whom he was in contact that had read and used it. A very good friend of his even owned a copy,” Fiorani said.

Plus, hints of the work abound in da Vinci’s drawings and journals, as he considered how to use variations of light and shade to capture what was going on in someone’s mind.

“If we imagine that he did read this book, suddenly we have an explanation of his art as a youth and throughout his life, an explanation of many of his writings, and why he was so interested in light, shadow, color and atmosphere,” Fiorani said. “We don’t have the ‘smoking gun,’ but conceptually, it’s very compelling. I am not the first one to suggest this, but I believe I am the first one to make the case as strongly as possible.”

It is possible, but difficult, to see the Mona Lisa without a crowd.

Because so much has been written about da Vinci, Fiorani is always working to keep herself grounded in the basics – in this case, the details of his work and everything she can observe firsthand about how he used light and shadow.

Of course, observing da Vinci’s work firsthand is no easy process; his paintings are among some of the most valuable and most closely guarded in the world.

“In order to study them the way I wanted to, I needed to see them without glass or frames,” Fiorani said. “I was able to do so for almost all of them – a work of years.”

To see the Mona Lisa, for example, Fiorani flew to France (before the pandemic) and joined a handful of fellow art historians there for the same purpose. For one day only, conservators carefully removed the painting from its frame and case, displaying it only on an easel and, later, on a flat table for close inspection.

“When I finally saw it flat on the table, without anything around it, that was the first time I saw it as a painting rather than as an icon,” Fiorani said. “It was one of those very special days.”

Da Vinci probably wouldn’t be your favorite boss.

Asked to recount other tidbits she has learned about da Vinci, Fiorani acknowledged that he likely would not win any “Manager of the Year” awards, genius though he might have been.

“His workshop was probably a tough place to be,” she said. “He played favorites, and stoked competition among his pupils and his assistants.”

Da Vinci’s pupils and assistants did most of the actual painting, she said. There are only a handful of known works actually painted by da Vinci himself.