University of Virginia psychology professor James Coan has vivid memories of the massive heart attack that almost killed him, the “widow maker” that had doctors rushing to put a stent in his heart before it was too late. Two years later, he says he will never forget the soothing physical contact of the nurse who grabbed his hand and stroked his forehead when he feared he was moments from dying.

That experience, along with Coan’s neuroscience research on the brain mechanisms that link social support to our health and wellbeing, inspired him to design “Why We Hold Hands,” an innovative, popular new course for first-year students.

The creative design of Coan’s course reflects the College of Arts & Sciences’ new approach to a liberal arts curriculum. First-year students take innovative Engagements seminars developed and taught by some of the College’s top faculty. The Dean’s Office typically appoints these College Fellows for two-year terms and encourages them to develop their dream courses in collaboration with colleagues from other academic disciplines. Philanthropic support funds others to teach the Fellows’ departmental courses while they focus on providing an enduring educational foundation for incoming students.

The unique topics selected by Coan and the other Fellows introduce first-year students to the standards of critical thinking, scientific research and reasoned debate that will guide the four years of their education on Grounds. In “Why We Hold Hands,” Coan combines the scientific underpinnings of how — at the elemental level of brain function — people soothe each other’s fears and anxieties with a broader exploration of how handholding and social relationships affect our sensory experiences, the lengths of our lives and everything in between.

Plus, the value of singing with one another. (More on that later.)

“We start the class talking in broad strokes about the methods of science, its social norms and the ethics of those norms, as well as some of the nitty gritty methods applied to behavioral ecology and the evolution of human brains,” says Coan, whose influential work has been covered in prominent journals like Science and Nature, as well as by The New York Times and other national media outlets.

University of Virginia psychology professor James Coan teaches a popular Engagements seminar based on his research on the brain mechanisms that link social support to our health and wellbeing. (Photo Credit: Stephanie Gross — http://www.stephaniegross.com)

“But we also have to study human cooperation, we have to study game theory, we have to study the evolution of social norms to begin to understand why one hand would clasp another, because it doesn’t have an obvious function in and of itself.”

Engaging the creative side of science

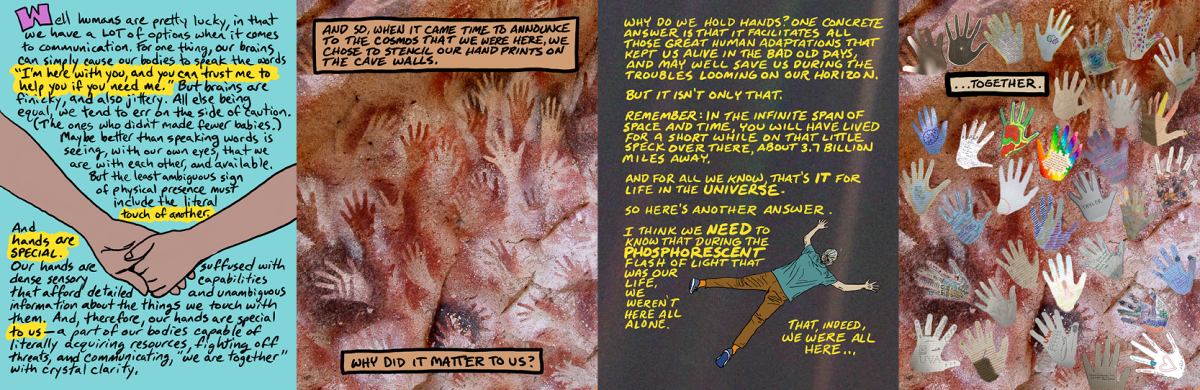

During a semester when pandemic restrictions require holding the class online, the irony of studying and discussing the fundamental value of human contact and real-world social interactions is not lost on Coan’s students. Yet, through the writing of personal reflection essays, poems and other creative projects inspired by the scientific readings — some of which Coan, an accomplished illustrator, has illustrated in graphic novel form — students say they absorb the seminar’s complicated scientific principles much more deeply.

The “Why We Hold Hands” class includes a series of scientific lessons illustrated in graphic novel form by Prof. James Coan, an accomplished illustrator.

“Getting in touch with my creative side and combining that with science is not something I’ve necessarily done before, but that was something I really enjoyed about Prof. Coan’s class,” says Carolyn Grimm, a first year from Northern Virginia whose family moved to the U.S. Virgin Islands six years ago. “The discussion portion of the class has been very engaging also, because it’s made me develop opinions about what we’re learning. As a result, I’ve retained the information so much more, because it’s something I enjoy.”

That’s the value of the New Curriculum and its interdisciplinary approach, Coan says.“Chopping up human intellectual activities into these different departments created the illusion that there was something really different between disciplines, and it represents a misunderstanding, at the very least, of science and how science is done,” Coan says.

"Science is fundamentally a creative process, not unlike writing poetry or composing music. You have to sit there as a scientist and repeatedly, over and over, through your career, imagine the way that the world could be, that you don’t know is true or not yet. So you’re basically using your imagination and generating these hypotheses and these models to envision a world that you don't know exists yet. And that’s hard, creative work.

— Psychology professor James Coan

Second-year student Xavon Stanley says he was attracted to Coan’s seminar last spring because of his interest in evolutionary biology. A first-generation college student from Martinsville, Virginia, Stanley is considering pursuing a master’s degree in education after completing his undergraduate degree in biology.

“I think Prof. Coan’s class gave me a much more personal appreciation for a lot of the things that we take for granted about our evolutionary history as a species,” Stanley says. “If you take a traditional evolutionary psychology class, you’re going to learn the scientific theories behind everything — which you get in this class — but you’re not necessarily learning the things that relate to your personal life.

“Prof. Coan’s class definitely made me appreciate social interaction and offered a lot more understanding that being social is something that is ingrained in our nature. It’s one of the things that makes humans, our ability to share ideas and our ability to even express intimacy on levels that aren't necessarily physical.”

Bonding students through song

Another teaching innovation introduced in the seminar is an invitation for Coan’s students to sing aloud, in front of their classmates. The “assignment” was inspired by the videos Coan saw from Italy, with people stepping out on their balconies to lift the morale of their neighbors by singing and playing instruments during the pandemic lockdown.

At the suggestion of his young daughter, Coan asks his students, one by one, to sing “Ah, Poor Bird,” an English children’s song.

“It's not really a digression, because singing, like handholding, is one of the things that we’ve come to understand that humans do to signal cooperative potential, bonding, closeness and solidarity in dealing with everything from war to famine to natural disasters,” Coan says.

This semester, with students taking the class remotely, Coan had students send him audio files they had recorded of themselves singing “Ah, Poor Bird.”