While women represent only about a third of the world’s research scientists today, that number is sure to increase dramatically if the number of women graduating with degrees in the sciences from the University of Virginia’s College of Arts & Sciences is any indication. Last year alone, the number of women graduating with bachelor’s degrees in fields like biology, chemistry and physics increased nearly 20% over the University’s previous 10-year average, almost double the increase in male graduates.

In addition to having award-winning female researchers and educators on the faculty and a strong contingent of women in leadership roles in all of the College’s science programs, one of the most important factors driving the increase in interest in the scientific disciplines, according to Laura Galloway, Commonwealth Professor of Biology and the College’s associate dean for the sciences, is the influence of strong role models among the University’s graduate students who are setting a high bar as researchers and playing an active role in mentoring the students who may soon walk in their footsteps.

“Role models matter,” Galloway said. “Many of our science programs have outreach programs that are showing younger generations this is what a UVA chemistry major looks like and this is what a UVA physics major looks like. We can’t underestimate the importance of that kind of outreach for the next generation of scientists.”

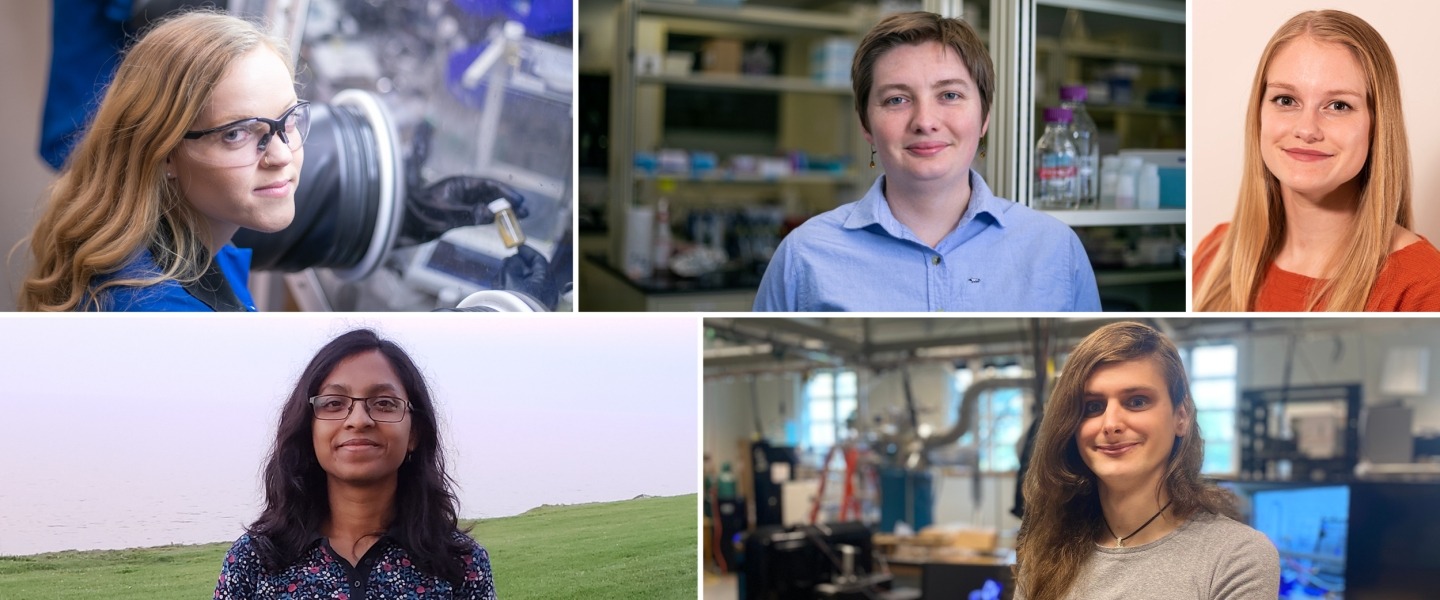

Meet just a few of the outstanding women who have earned advanced degrees in the sciences this year as members of the College’s Class of 2022.

A Rising Chemistry Superstar

Kelsie Wentz’s dream has always been to have a career in the sciences. This spring she graduated from the University of Virginia’s Graduate School of Arts & Sciences with a Ph.D. in chemistry as her department’s winner of the Adam Ritchie Outstanding Graduate Student award.

The Class of 2022's Kelsie Wentz received her Ph.D. this spring and graduated as the Department of Chemistry's Adam Ritchie Outstanding Graduate Student. Credit: Molly Angevine

The Class of 2022's Kelsie Wentz received her Ph.D. this spring and graduated as the Department of Chemistry's Adam Ritchie Outstanding Graduate Student. Credit: Molly Angevine

Wentz’s research is focused on elements from a portion of the periodic table called the p block, which are good conductors of heat and electricity. In the lab, she synthesizes new molecules featuring elements like boron and germanium that are abundant in nature, are understudied by chemists and have the potential to play an increasingly important role in the future of technology. The molecules she develops will enhance the structural and electronic properties of new materials that will be used in making organic light emitting diodes and materials that will make computer or cellphone displays brighter and more flexible. They may also help make technology less expensive or more energy efficient.

According to Wentz, there’s still a lot of work to be done, but she’s playing an important part in creating a foundation for engineers who will use her research to build new devices.

“I’m working on making fundamental advances, isolating novel molecules and studying them for various materials applications,” Wentz said. “You don’t know what something is going to be useful for until you study it, and that sense of discovery is what I enjoy and what makes chemistry interesting.”

“Kelsie has trained not only undergraduates in the group, but she’s helping to train the other graduate students as well. She’s a model citizen for the department and an excellent leader,” chemistry professor Robert Gilliard said.

After graduation, Wentz will pursue a career in research chemistry. As a first step toward that goal, she recently accepted a postdoctoral position at Johns Hopkins University.

“I know she is going be a superstar,” Gilliard added. “Her future is very bright.”

The Power of Network Support

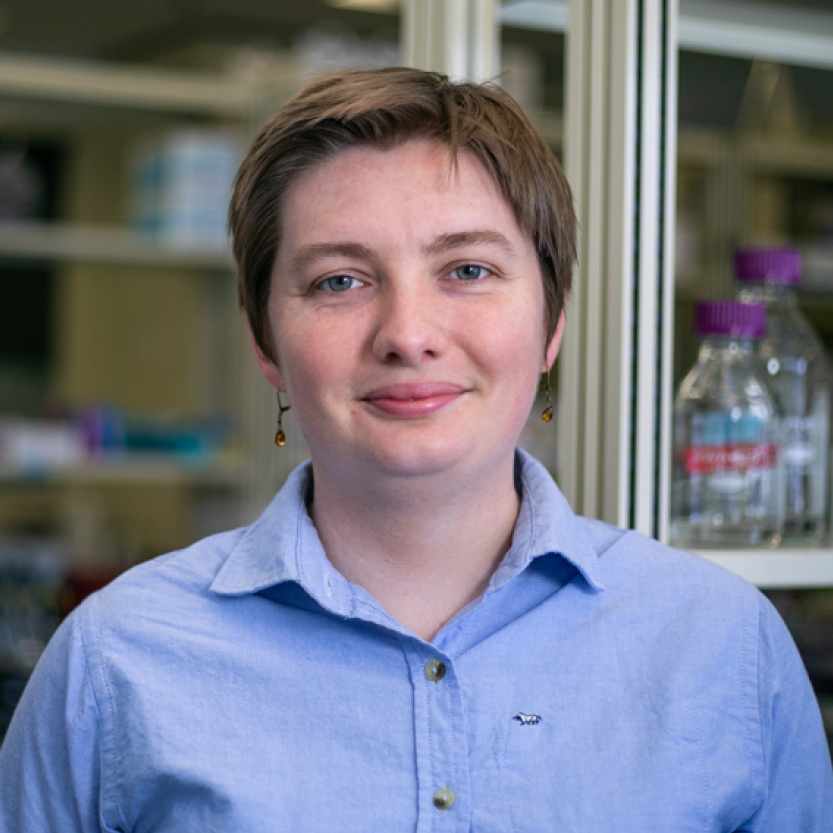

Coming to UVA to pursue a Ph.D. in biology was like coming home, said Phoebe Cook, who graduated this spring. After taking a course in evolution as an undergraduate at Swarthmore College in Philadelphia, she knew she had found her path, and a summer undergraduate research experience at the UVA’s Mountain Lake Biological Station in remote Giles County, Virginia, convinced her that UVA was where she needed to be.

As a graduate student, Cook has published several papers in high-profile academic journals for her work with the forked fungus beetle, a small insect common throughout eastern North America that spends its life on the fungus found on rotting logs.

“They don’t seem that interesting, but they actually have more complicated social lives than you would think,” said Cook, who is interested in how social networks evolve in the animal world and why they matter.

Phoebe Cook, who studies animal behavior and their social networks, graduated this spring with a Ph.D. in biology from UVA's Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Credit: Molly Angevine

Phoebe Cook, who studies animal behavior and their social networks, graduated this spring with a Ph.D. in biology from UVA's Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Credit: Molly Angevine

Cook observes the interactions of groups of beetles, mapping the connections they make with each other to determine which are more social and which prefer to keep to themselves. She’s also interested in whether those roles remain consistent when individual beetles are moved from one box to another and in how the personalities of individual beetles affect the health and success of the networks to which they belong.

Her research has led her to conclude that, rather than being shaped by environment, sociability is a trait unique to individual beetles and that the personalities of those beetles play a large part in influencing how their networks behave even when they are introduced to a new community. Her findings also suggest that while highly social individuals play a bigger role in spreading problems like disease throughout a population, they can also be very effective at spreading useful information and helping their networks take advantage of the resources available to them.

As a graduate student, Cook explored a variety of opportunities to improve her skills in the classroom, and when the time came to decide which direction to pursue after graduation from UVA, Cook accepted a position as an educational consultant with Carnegie Mellon University’s Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence & Educational Innovation.

According to Taylor Nystrom, one of Cook’s colleagues in the Department of Biology, Cook has been a model for those who envision a more inclusive academic environment.

“Phoebe’s been a very supportive part of her own social network and her community, and that’s something I really admire about her,” Nystrom said. “She has also had an incredible impact on a departmental level and at the University level.”

An Innovator in Global Health

Biologist Audrey Brown has earned her Ph.D. for her work in cellular biology and her research on how changes in a body’s metabolism affect the drugs used to treat malaria.

The disease is caused by a single-celled, mosquito-borne parasite, and like a virus, it can adapt to survive a variety of challenges that could wipe it out completely. Significant strides have been made in treating the disease, but due to the parasite’s ability to continue to develop drug resistance, the disease still claims the lives of nearly a million people every year.

“I’m interested in how these parasites are stressed in the actual context of a human infection versus how they respond in a dish in the lab. There are some big differences,” Brown said. “I want to understand whether or not the stressors that the parasites are subject to in a human infection may change it and give it the ability to survive a little bit better.”

Audrey Brown graduated this spring with a Ph.D. in biology. Her research could lead to new insight into the treatment of malaria. Credit: contributed

Audrey Brown graduated this spring with a Ph.D. in biology. Her research could lead to new insight into the treatment of malaria. Credit: contributed

“Exercise is a stress on the body, but it’s not bad for you. It’s actually really good for you to have a little bit of stress,” Brown explained. “It’s only when you take that stress too far and you over exercise that it becomes bad for you. In the same way, the stressors that the parasites are experiencing in the body of a person they’re infecting might actually help [the parasites] survive a little bit better.”

This summer, Brown will continue her research in infectious disease as a post-doctoral fellow with the UVA’s School of Medicine.

“Audrey is unafraid of challenges and undaunted by failure,” said Associate Professor of Medicine Girija Ramakrishnan, one of Brown’s advisors. “She absolutely does not give up and has therefore been able to make a big mark in the field of malaria research by developing a protocol for isolating malarial parasites at a specific life stage that is of great value to the field. She has also used this protocol to reveal valuable new insights about malarial drug resistance. I think she is a great role model for what a student can do if they set their mind to it.”

Driven by Curiosity

Physicist Preetha Saha looks back at some of the women scientists she encountered as an undergraduate as being important role models to her.

“When you’re 18 or 19, it’s very inspirational to see them and think, okay, this what I want to do with my life.”

Saha, who graduated this spring with a Ph.D. in physics, earned her undergraduate degree and her master’s degree in India. She knew she wanted to pursue a Ph.D. in physics, and she was particularly interested in the subject of superconductivity, which is the capacity of certain materials to conduct electricity with no resistance when they are cooled to extremely low temperatures.

Her research led her to an interest in condensed matter physics — how the electromagnetic properties of atoms create objects that we think of as solids or liquids. As a student of physics professor Gia-Wei Chern, she specialized in the study of a phenomenon known as frustrated magnetism, which explores the unique collective behavior of atoms and their electromagnetic properties when combined to form certain types of matter that should be magnetic at low temperatures but are not. Her work has helped identify several novel properties of these configurations of atoms and has advanced science’s understanding of why they behave the way they do.

Physicist Preetha Saha completed her Ph.D. at UVA this spring. Her work in computational condensed matter physics could lead to a better understanding of the physical world at its most fundamental level. Credit: contributed

Physicist Preetha Saha completed her Ph.D. at UVA this spring. Her work in computational condensed matter physics could lead to a better understanding of the physical world at its most fundamental level. Credit: contributed

She enjoys the work even if it’s not clear yet what role it will play in the future. It’s an important step that could lead to new directions for research in advanced electronics and someday to improvements in the science of superconductivity and the technological advances needed to transmit electricity more efficiently. There’s still much that science doesn’t know about the nature of the matter Saha studies, but as an experimental physicist, she maintains that the important thing is to be “curiosity driven.”

Much of her work as a physicist has involved computational physics which uses computers to develop scientific solutions to highly complex mathematical problems, and those skills are important in a growing number of fields.

“Most of my work during my Ph.D. was in simulations, analytics and modeling,” Saha said. “I love learning physics, but I also love the simulation aspect of it, like exploring what algorithms would make my program run faster and reduce the operating costs.”

When she was offered a job modeling financial data and optimizing assets for BlackRock, the world’s largest financial-asset management firm, she jumped at the chance to apply her world-class research skills to a new endeavor.

At the Precipice of Discovery

Allison Zec came to UVA to take advantage of its strong nuclear physics program and its faculty’s ties to research facilities like the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility in Newport News, Virginia, and the Brookhaven and Oak Ridge National Laboratories. As a graduate student, she worked with a device called a Compton polarimeter, which is used to study the impact of charged atomic particles on beams of light, an interaction that will help scientists better understand the physics of neutron stars.

Zec is especially interested in the applications of nuclear physics to fields like medicine and nuclear power, but she is primarily interested in what the study of physics can reveal about nature at its most fundamental level.

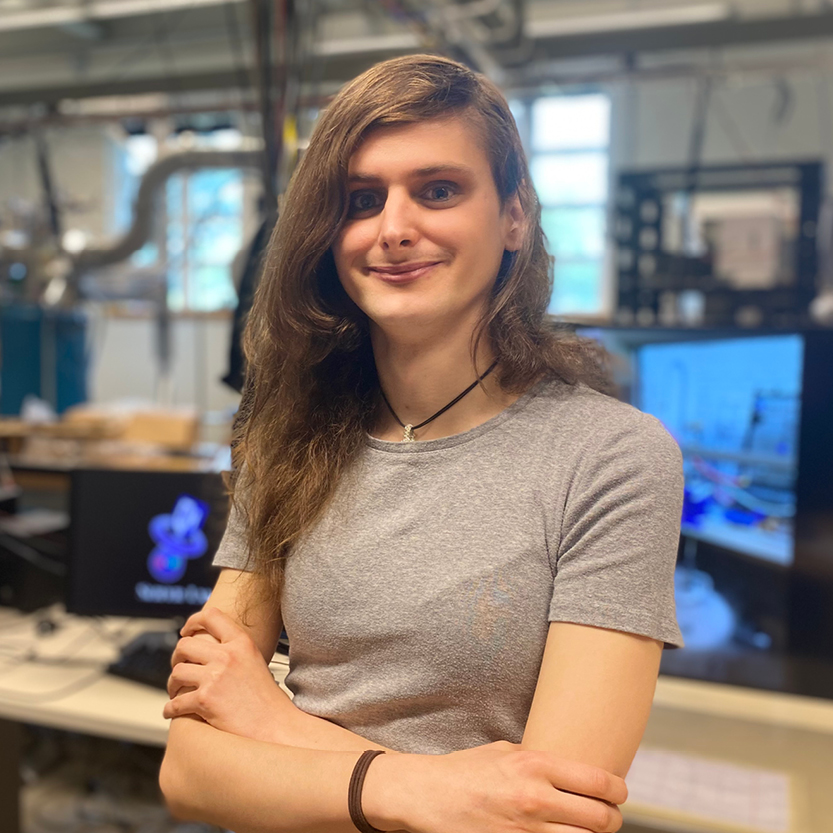

The Class of 2022's Allison Zec completed her Ph.D. this spring. Her research involving the physics of neutron stars is helping advance our knowledge of the physical forces at work in the universe. Credit: contributed

The Class of 2022's Allison Zec completed her Ph.D. this spring. Her research involving the physics of neutron stars is helping advance our knowledge of the physical forces at work in the universe. Credit: contributed

“Boiled down to its simplest terms, I’m studying how objects move and interact with each other,” Zec said. “There’s a lot about that interaction that we don’t understand, but we are on the precipice of developing new knowledge and new theories about how matter in the universe holds itself together.”

Kent Paschke, a professor of physics, director of graduate studies in physics at UVA and Zec’s advisor, noted that experimental physics often involves a large number of people working in high-stress situations. The department works hard to make sure everyone’s input and concerns are heard and respected. In addition to recognizing Zec as a researcher of the highest caliber, he commended her for her work as a community builder at UVA.

“Allison was an important and supportive part of our research efforts,” Paschke said. “And she was the social glue of our team.”

Zec felt just as strongly about the importance of community in the sciences.

“I came to UVA to study physics, but I stayed because there were so many people who I felt confident being around and being myself around,” said Zec, who transitioned her gender during her time at UVA.

Zec will pursue a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of New Hampshire starting this summer, and after that, she hopes to pursue a career as a staff scientist at a national research laboratory.

“She’s got the ability to have terrific career in nuclear physics research,” Paschke said. “Her future is in her hands.”