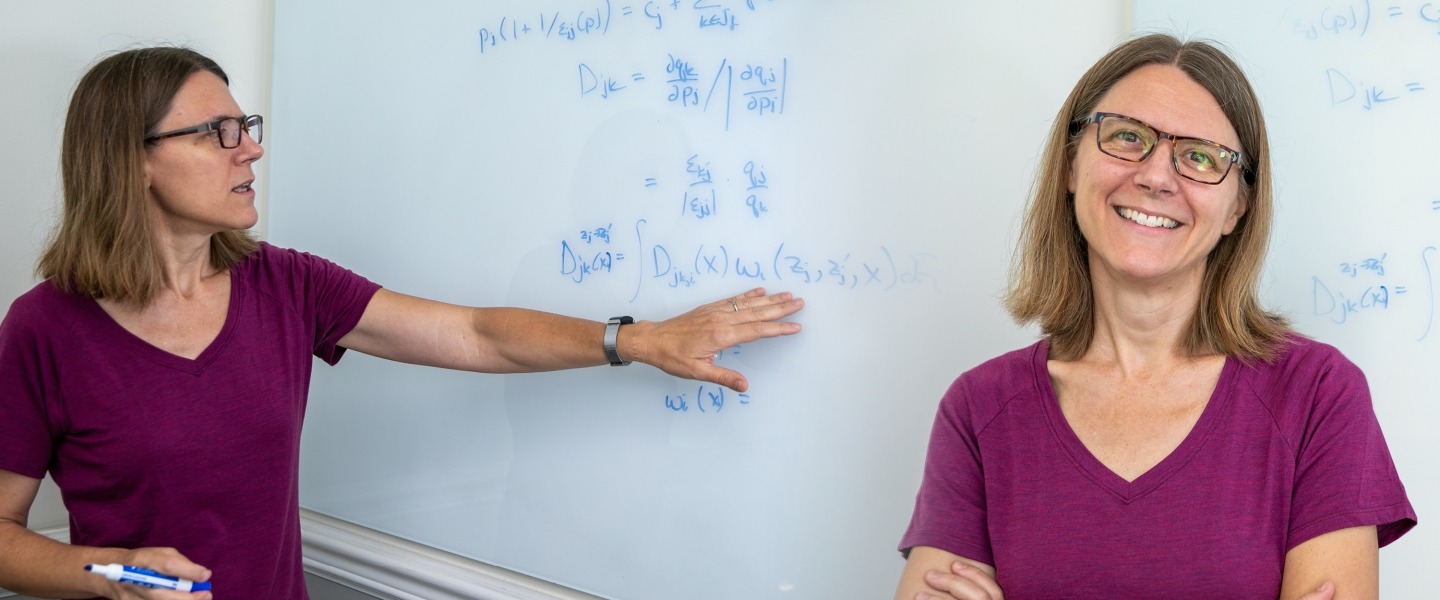

Noted antitrust economist Julie Mortimer joins the faculty of UVA's College of Arts & Sciences this fall as the Department of Economics' Kenneth G. Elzinga Professor in Economics and the Law. (Photo credit: Caitlin Cunningham)

Noted antitrust economist Julie Mortimer joins the faculty of UVA's College of Arts & Sciences this fall as the Department of Economics' Kenneth G. Elzinga Professor in Economics and the Law. (Photo credit: Caitlin Cunningham)

If you’ve taken an intro course in microeconomics at UVA over the last 50 years, there’s a good chance you know Ken Elzinga, the University’s Robert C. Taylor Professor of Economics and a specialist in antitrust economics, the branch of the discipline that informs the laws that protect businesses from unfair business practices like monopolies. In a career with the College of Arts & Sciences that spans more than a half century, Elzinga has taught over 50,000 students, more than any other UVA professor. This summer, the Department of Economics announced that, with the help of the College’s alumni, it had established an endowed chair honoring his achievement and that it had selected economist Julie Mortimer to fill the postion.

“We are thrilled to bring such a prominent and innovative scholar of antitrust and competition to fill the Elzinga Chair,” said Leora Friedberg, chair of the Department of Economics. “Professor Mortimer has a stellar record of publication, teaching, and mentorship that will carry forward the University’s legacy on this critical topic. This would have been impossible without the support of generous donors committed to the excellence of our faculty.”

Elzinga expressed his satisfaction with the hiring of a scholar of Mortimer’s caliber who is as dedicated to her students as she is to her research.

During his career spanning over 50 years at UVA, Ken Elzinga has taught the fundamentals of economics to more than 50,000 students.

During his career spanning over 50 years at UVA, Ken Elzinga has taught the fundamentals of economics to more than 50,000 students.

“I am delighted and honored that Professor Julie Mortimer will join the Department of Economics this fall as the first holder of the endowed chair that bears my name. Her scholarly publications give her a national reputation, and to top it off, she cares about teaching,” Elzinga said.

We spoke with Mortimer to learn more about her work and what attracted her to UVA and the Elzinga professorship.

Q: How would you describe your work as an economist?

A: I work in an area of economics referred to as industrial organization. The idea is that we’re studying how firms organize getting goods to market, their supply chains and their retail and manufacturing.

Antitrust economics is a part of that, and I bring that up right away because it’s something that Ken Elzinga is so widely known for. His work has had a big impact not only at UVA but in the world at large. Antitrust economics is focused on what I think of as horizontal issues like whether a merger could have an impact on how firms compete over prices. But there’s also a vertical component to antitrust, looking at the types of contracts that manufacturers might sign with retailers or that a drug manufacturer might sign with a pharmacy benefits manager and other arrangements between upstream and downstream firms.

Q: How did you get interested in these issues?

A: I went to college thinking that it would be amazing to be able to use statistics and math to understand the world, and discovering that you could actually have a job that used those skills kind of blew my mind. I grew up in a small town in Montana, and you didn’t see people in those kinds of jobs there. But I knew that they existed. My thesis advisor, Scott Bierman, was actually a UVA graduate. He was also one of Ken Elzinga’s teaching assistants at UVA.

But what really excited me about everything that I learned in my courses and in writing my thesis was seeing the application of what I was learning. When I started down the statistics route, it very quickly got theoretical, and I lost the connection to policy and to the impact of the research on the real world. What I found was that I enjoyed doing the math, but economics gave me a way to make sure that it mattered and that it was going to be impactful for policymakers, for legislators, for litigators and for anything that affects the way we structure our economic life.

Q: From your perspective, what are some of the biggest economic challenges companies face in the next few years?

A: I think the landscape right now is challenging because of the amount of uncertainty firms face. There’s uncertainty about the stability of international supply chains and about the way international relations will evolve, but there’s also uncertainty about domestic policy. I feel that we’re in a moment right now where there’s more uncertainty about domestic policy than has been the case in the past, for example whether things like our antitrust policies will be upended. That’s something that’s hard for firms to navigate.

Q: Do you see that uncertainty impacting legislation?

A: I’m not in the trenches on it, but there’s been an effort in Congress to write either new regulations or new antitrust statutes to address concerns about competition between big tech companies. Going back 100 years, we’ve seen firms in the past like Standard Oil that dominated their markets, but I don’t know that they were as dominant as Google or Facebook or Amazon are today. We’ve had periods with a high concentration of dominant firms before, but we’ve never navigated the kind of dominance we have right now. The big difference with places like Facebook and Google is that they have such large networks of users, they have all the data from those users, and they can create algorithms that are going to be more informed than something a new entrant into the marketplace might have. For academics, the concern is whether or not that changes things, and if so, how? And depending on how it changes things, do we change the laws? And that’s hard to know. One of the things I worry about right now is that there’s an urgency to do something about this, which I understand, but it’s legitimately hard to figure out what needs to be done.

Q: Some of your published research focuses on the role digital technology plays in the retail industry. What are some of the most compelling issues in that arena?

A: One of the things that digital technology makes possible is new forms of contracting. We’re now able to monitor transactions that we couldn’t have monitored before, and because we can monitor them, we can write better contracts, and we can write different kinds of contracts. Distributing content like movies, music or photographs digitally, you’re faced with different challenges in terms of intellectual property concerns. And there are important differences from the days when we used to just sell a cassette tape or sell a CD. That creates opportunities, but it also creates challenges for content producers. If you search for a picture of a kitten on Google, you’re going to find a gazillion pictures of kittens, and some of those images are copyright protected. Thirty years ago, if you wanted to use an image, a photographer would have licensed you the photo. But now it’s Google that makes these images available. Now someone can take a screenshot of it or download the image without the photographer ever knowing.

From the user’s perspective it’s also challenging. Some of the cases I’ve researched are, for example, like someone running a bakery who hires a developer to create a website. The developer comes back with a nice-looking site with a picture of a baguette on it, and it looks great. The baker puts up the website and then suddenly someone’s emailing them saying, “Hey, you violated our copyright.” It’s a very difficult landscape to navigate. A lot of users don’t know how to license content, and content producers don’t know how to reach the users. If you’re a photographer, how do you find a developer who’s putting together websites for bakeries? We clearly have access to much better content in all of these spheres than we used to, and there’s enormous opportunity, but the challenges are also significant.

Q: You talked a bit about your prior UVA connection, but were there other things that attracted you to joining the faculty at UVA?

A: I really like the department. The whole department seems like a group that I will enjoy working with, and that was a big part of the attraction for me. Charlottesville also just seems great, just amazing, and you know, I’m excited about exploring the area. But the number one reason, and this has been my guiding star in every teaching-related career decision I’ve ever made, is the students. I have really been impressed with the students at UVA — both the undergrad and the graduate students. I’ve just been impressed by them. I like them, I’ve learned from them and I find that they’re capable and engaged. And I don’t know what the right word is, but I have a teenager, so the word that keeps coming to my head is “vibe.” There’s a vibe with the students that just feels both productive and exciting.

Q: How did the Elzinga professorship impact your decision to come to UVA?

A: I have had a lot of connections, indirectly, to Ken’s work. I know a lot of colleagues who were students of his, but to be honest, I didn’t know whether I would be an interesting candidate to the committee because I haven’t done litigation work. I have a husband who works in litigation and expert witnessing, so I know that world, but I’m not in it. But what I am really involved with and what I’m really passionate about and committed to is teaching. In that sense, it was the connection to the teaching that makes the Elzinga professorship special. I really like working with students, so I spend a lot of time with students and that part of it. The connection to Ken’s teaching, was really meaningful for me.

The flexibility that the chair gives you is a really important part of that too. It’s the crucial ingredient to being able to continue the synergistic dance between research and teaching. If you’re not doing research, then you’re not staying abreast of everything that’s happening and you don’t have your finger on the pulse of what matters to policymakers and what the world needs, and I need to be able to do those things to have an impact on my students. The chair gives you time to do them.

Q: What research projects are you working on now?

A: I’m working on a couple of big areas. One area is incorporating some of the techniques that computer scientists have used in facial recognition to capture patterns of demand across markets where there are multiple products without needing a model with certain parametric assumptions. We’re working with snack foods and automobiles and using machine learning to help us see — if you get rid of the Snickers bar from a vending machine, for example — where people go instead. The question is, if I can do that with a few top-selling products, can I successfully then tell you about substitution across the whole vending machine? That’s essentially how Facebook connects faces, so I’m interested in the algorithms and machine learning methods of approximating complicated things with simpler things. Basically, I’m trying to get better estimates of patterns of substitution and demand in markets.

I’m also doing a lot of work on advertising these days and the contracts between advertisers and networks. Basically, content producers of any sort have these really fascinating market structures where some of the advertisers who have been advertising for a long time like your Procter & Gambles of the world have these longstanding relationships that the industry describes as being very important to the pricing of ads and the placement of ads. So, I’m analyzing what that means for outside policymakers: if there were a new consumer goods company that wanted to enter the market, how those relationships would affect them.

Q: What are you looking forward to most in your first year at UVA?

A: Being done with my move! And I’m looking forward to meeting and getting to know my colleagues and my students. Every time I’ve been to UVA, I’ve felt comfortable and happy there. It seems to function well across its many parts, so I’m looking forward to getting a feel for that. Basically, I’m looking forward to finding my way around, finding a dentist, you know, all those things.

And I’m looking forward to making new friends! I guess that’s what it really boils down to.

More Exciting News from the Department of EconomicsRecently, the Economics Career Office, or “ECO”, has been named in honor of Edwin T. Burton, esteemed faculty member of the department. Naming ECO for Burton was proposed by alumnus and lead donor Drew McKnight who, together with other grateful A&S alumni and parents, contributed $1 million. They join a committed group of A&S alumni and friends in an ongoing effort to permanently endow the office by raising at least $3 million. Read more here. |