Ask a roomful of college graduates which of their undergraduate courses was their favorite, and you’d be hard pressed to find one who waxes nostalgic about introductory chemistry. Traditionally, it’s a tough course that involves math, memorization and long hours in crowded lecture halls where students who don’t keep pace can find themselves in trouble very quickly.

Fourth-year Makenzie Scanlon took general chemistry in her first year as a chemistry major. She had taken the AP exam, but she hadn’t passed it, and she didn’t feel confident that she understood the material well.

“It’s memorization,” she says about the course she was expecting. “It’s geared toward a certain type of learner. You listen to a lecture, read a textbook, and synthesize the information yourself, and not everyone learns that way.”

After a high school International Baccalaureate program in chemistry, physics major Ali Verster was confident that she could succeed in college-level chemistry, but she didn’t expect it to be easy.

In their first year at UVA, both students signed up for a newly redesigned course offered by UVA’s Department of Chemistry. When they registered for the course, neither one expected much more than to survive it. Instead, the new approach to teaching a challenging subject has not only shaped their undergraduate experience, but has also positively impacted student success, making STEM degrees more accessible for students from all backgrounds.

Rethinking Chemistry Education

Faced with the prospect of teaching general chemistry in her first year as a faculty member at UVA, Professor Linda Columbus didn’t want to teach the material the way it had been taught to her.

“We’re instructing as we did 50 years ago,” she says. “The world is changing, our understanding of chemistry is changing, and the ways that we communicate are changing, but the way we teach is not.”

Moreover, the typical general chemistry lecture hosts nearly a thousand students, 96 percent of whom go on to majors in other fields, like engineering or a pre-med track. Columbus realized that the course wasn’t aligned with the needs of the majority of her undergraduates.

“They absolutely need to be taught what a chemist will need,” she says, “But we had to think about what all the other people would need. What do you want them to walk away with?”

Her interest in reimagining how chemistry education might look in the 21st century led her to a year-long collaboration with Gail Hunger, a senior instructional designer with the Arts & Sciences Learning Design & Technology group, a team of specialists employed by the College to bring technological and pedagogical innovation to classrooms at the University.

Using a research-based educational model, surveys and focus groups with students, and input from chemistry department faculty, Columbus and Hunger developed a new kind of chemistry course that combines a traditional lecture with hands-on problems and active learning spaces. The new format gives students the opportunity to solve problems in a way that helps them understand the principles of chemistry and to think more deeply about the subject, which undergraduates are rarely asked to do at the introductory level — an approach that’s more challenging but also more rewarding.

Chemistry professor Linda Columbus (left), and instructional designer Gail Hunger (right) collaborated to develop an innovative, active-learning approach to teaching chemistry that is dramatically increasing student success rates.

In this novel approach to teaching introductory chemistry, students meet twice a week, once for a traditional lecture and once in an active-learning “Expo” where they meet in small groups. A professor or graduate instructor and a team of undergraduate TAs who know the material work closely with students as they apply what they’re learning to real problems.

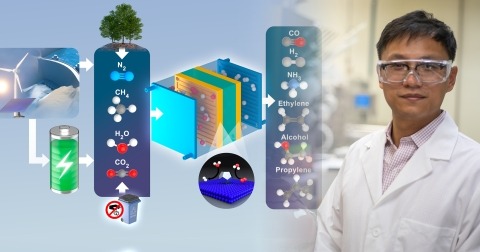

Assistant Professor Kevin Welch, who now teaches the course Columbus and Hunger designed and continues its development, explains “One of the goals of this course is to bring modern approaches to chemistry into the classroom, to show students from the very beginning what tools modern chemists use.”

In Welch’s course, the Expo gives him the opportunity to provide his students with real scientific software and data from classic experiments, letting his students see how scientific discoveries are made — an approach that demonstrates that what they’re learning has real-world implications.

Making Large Classes Small

One of the problems Welch grappled with before he began teaching the redesigned general chemistry course was how to make himself available to hundreds of students each semester.

“Being in a lecture hall with 500 students, a student can feel anonymous, that they’re lost in there, and we would see that,” Welch says. “We’d see students who would stop coming to class. They would struggle, and then they wouldn’t show up for an exam, and that would be the first time that I would notice that they were struggling.”

“We’ve eliminated the gaps, essentially, between the students from more and less advantaged backgrounds. It’s a testament to the fact that there’s nothing innate or insurmountable with students coming in with different experiences, and that we can, if we choose to do so, make sure that all students succeed.”

Josipa Roksa, professor of sociology and a senior advisor for academic programs with the Office of the Executive Vice President and Provost at UVA.

The active-learning Expo gave Welch the solution he was looking for. During a typical Expo, students break up into small groups to solve a problem presented by the instructor, enabling them to reach a solution they all agree on as the instructor and the TAs circulate through the room offering suggestions and insight to the groups. It’s an arrangement that helps them spot problems with comprehension and encourages students at all levels to bring something to the table.

“One of the main goals [of the Expo] is to increase the opportunities for students to interact with people involved with the course,” Welch explains. “In those 100-person Expos, there’s one instructor and then three or four undergraduate TAs who have been through the course before. Each becomes a resource that helps us identify when students are struggling.”

“It transforms the classroom experience,” Welch says. But, he adds, “It’s very different for the instructor in that you have to let go. You’re not just up there talking and controlling what everyone’s doing. You have to let the students go and do their own thing. It’s very powerful because you can get into much deeper questions, and your interaction with students is so much stronger.”

For chemistry professor Kevin Welch, who teaches general chemistry using Columbus and Hunger's format, the active-learning approach has increased student engagement even under the challenges posed by COVID-19.

And when the threat of the coronavirus closed Welch’s classroom, the new format posed few significant challenges.

“The students are handling it extremely well,” Welch says. “We had two exams last week. The students were able to complete the group exams exactly as they would in class and upload them to be graded.”

His TAs were also enthusiastic about the challenge, holding virtual office hours for students and video conferencing with Welch to work through the new format.

Surprising Results

While the redesigned chemistry course presented advantages to the chemistry faculty who teach it, Columbus and Hunger wanted to be sure that the course was actually better for students. To answer that question, they sought help from Josipa Roksa, a senior advisor for academic programs with the Office of the Executive Vice President and Provost. Roksa is a sociologist who studies higher education with a focus on student success and equity. To evaluate the success of the new course, Roksa surveyed students and analyzed grades and other learning outcomes. The results are astounding.

“Since the class has been redesigned,” Roksa says, “student success rates have increased dramatically.”

Josipa Roksa, a senior advisor for academic programs with the Office of the Executive Vice President and Provost, evaluates the impact of the active-learning format based on a variety of learning outcomes.

The number of students who typically struggle in the course has dropped by two-thirds, and the number of students who continue to the second semester has increased substantially.

Not only that, she says, “We’ve eliminated the gaps, essentially, between the students from more and less advantaged backgrounds. It’s a testament to the fact that there’s nothing innate or insurmountable with students coming in with different experiences, and that we can, if we choose to do so, make sure that all students succeed.”

A Clear Advantage

For students who want to see themselves in a STEM-oriented career but may not have the experience or the confidence that they can succeed, the active-learning model is helping them break through those barriers.

After taking the class in her first year, Makenzie Scanlon went on to work as a teaching assistant for the course for two more years, seeing first-hand the impact the course was having on students like herself. Her experience helped her realize that her dream of going to medical school wasn’t out of reach.

“I had a hard time seeing how I could offer something to a medical school, but coming in and being able to synthesize my thoughts, and being able to collaborate with others and contribute and learn the material, I think it contributed to my confidence,” Scanlon says.

For students like Ali Verster, who approached the course with confidence and experience, the opportunity to develop her critical-thinking skills and her problem-solving skills was something more than she expected from an introductory course. As she went on to take more advanced courses like organic chemistry, she felt she had a clear advantage over other students who hadn’t had the benefit of the active-learning experience.

Looking back to her first year, she recalls that several of the students in her dorm took the traditional lecture, and every time they had an exam, she could sense the stress in the air.

“I never really had the same experience,” she says. “Instead of worrying about chemistry, I was enjoying it.”

“My favorite class of all of first year was general chemistry. If I could take any class at UVA again,” Verster says, “it would be this one.”