For students interested in STEM degrees such as science, technology, engineering and math, there’s nothing lonelier than sitting in the crowded lecture hall of an introductory science course struggling to absorb enough facts to pass the final exam. Generations of STEM students and faculty have accepted the experience as the best way to separate those who have an aptitude for success in the STEM fields from those who don’t, but that may be about to change.

After spending several years developing a new format for her introductory chemistry course with the help of faculty and staff colleagues across Grounds, UVA professor Linda Columbus introduced a curriculum that combines the traditional lecture-hall experience with active-learning exercises that focus more on developing real-world problem-solving skills than on rote memorization. The result has made the large class seem more like a small one, where students who are experiencing challenges are less likely to be overlooked. In the process, it has solved several of the persistent problems the traditional introductory science course typically presents. As a result, student performance has improved, inequalities in performance that existed between students from different cultural and educational backgrounds have declined, and the number of students who continue to take additional courses in chemistry has increased.

Columbus’ success hasn’t gone unnoticed. With the help of like-minded faculty taking leadership roles in other departments, the College has begun to explore ways to replicate Columbus’ results across the College’s introductory science and math courses, rethinking not just how science is taught but how faculty think about teaching.

Building a Better Gateway

When she first began teaching an introductory chemistry course at UVA, Columbus knew that the traditional approach wasn’t delivering the education her students needed. In the lecture hall she faced hundreds of students from different backgrounds, some who came from school systems with more abundant resources and had the benefit of advanced-placement courses or summer science camps and many who did not. She also recognized that her students were coming to the course with different objectives. A small number would go on to major in chemistry, but the vast majority were there because the course was required for another degree.

Columbus knew that it would be impossible for her to meet the unique needs of hundreds of students each semester and help them succeed in the course, and that helped her see that she needed the kind of skill set and insight that her training as a chemist hadn’t provided.

“We are hired because we’re researchers,” Columbus said. “But in order to deliver a better education to our students, I realized I either needed to have a Ph.D. in education or collaborate with someone who does.”

Reaching out to the College’s Learning Design and Technology team, she met Gail Hunger, a senior instructional designer employed to bring technological and pedagogical innovation to the University’s classrooms.

Hunger had already been thinking about many of the same problems.

“Everyone has a story about how terrible their introductory science courses were and how they accepted that that was how it was supposed to be,” Hunger said. “But I don’t think it has to be that way.”

The new course curriculum that Columbus and Hunger designed allowed Columbus the opportunity to engage with students in a way that she might with a smaller class size and allowed her to employ students who had already taken the course as learning assistants to help facilitate small-group discussions and to identify when students were having problems with the material.

“What we did was level the playing field by introducing the kinds of problems that no one had seen before. The curriculum doesn’t take things out of the content, it adds something that the courses didn’t have before, a layer of complexity and the kind of problem-solving challenges that you can’t solve by just Googling them.”

After teaching several sections of the course, the results were clear. The data showed dramatic increases in student success rates. There was also a substantial increase in the number of students who enrolled in the second semester of the course, and the learning gaps between students from different backgrounds and with different levels of preparation coming into the course were significantly reduced.

Moreover, rather than making the course easier, the data also suggested that students who had taken Columbus’ course were doing better in more advanced courses because they had already been introduced to the kind of problem-solving skills they would face there.

“It’s hard to understand how you could make the course something everyone could do well in even when some of the students are years behind others in the preparation they’ve had to take the course,” Hunger said. “What we did was level the playing field by introducing the kinds of problems that no one had seen before. The curriculum doesn’t take things out of the content, it adds something that the courses didn’t have before, a layer of complexity and the kind of problem-solving challenges that you can’t solve by just Googling them.”

Agents of Change

When news about the impact of Columbus and Hunger’s course redesign reached UVA’s Executive Vice President and Provost Ian Baucom, who was dean of the College of Arts & Sciences at the time, he reached out to Columbus and a handful of faculty members from other departments in the College to explore the feasibility of replicating similar course outcomes in other disciplines.

They formed a faculty coalition known as the Advance Fellows who were willing to exchange information on best practices in teaching introductory science courses, assess the appetite for adopting new teaching methods in their own departments and adopt the practice of teaching as a scholarly pursuit.

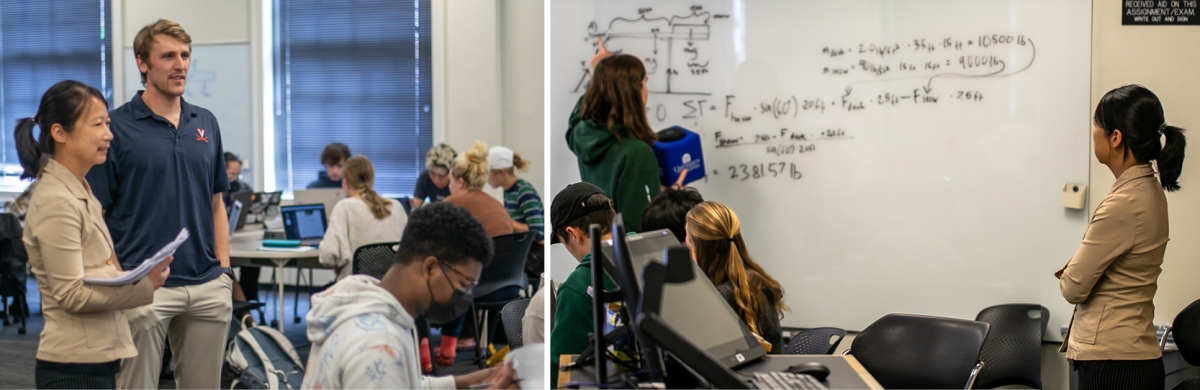

Like Columbus and most of her STEM faculty colleagues, physics professor and Advance Fellow Xiaochao Zheng was not trained as a teacher. When she was hired as a faculty member at UVA, she was prepared to teach physics majors who had the same interests and aptitudes that she had as an undergraduate, but she found it difficult to teach introductory physics to engineering and pre-med students who were only in her course because it was a prerequisite for other majors. Columbus’ success offered Zheng a new way to approach the challenges of teaching a diverse group of students with different reasons for taking her class.

Drawing on Columbus’ experience, she has incorporated some of those ideas into her own course. She still spends some of her time lecturing, but she also uses active-learning techniques like giving collaborative quizzes in which groups of students work together to arrive at and present their answers and giving homework and exams that require written answers instead of multiple choice. The approach tells her more about how her students are mastering the material, which helps her be more effective as an instructor.

“We still have a long way to go,” said Zheng, who is leading the effort in her department to transition all introductory physics courses to an active-learning format, “But we can never go back to the old way. Everyone knows that the traditional lecture isn’t working for the modern generation of students.”

In the Department of Biology, Advance Fellow Jessamyn Manson, the director of undergraduate programs, sees many of the same challenges in biology that Columbus faced in chemistry.

The active-learning model that Columbus and Hunger developed and its success in closing preparation gaps attracted her to the Advance Fellows program, but she too finds that the model is helping students see the value in a course that most have taken only to satisfy a degree requirement.

More than 70 percent of the 850 students Manson teaches in introductory biology each year are pre-med. Teaching them the value of subject matter that many students see as peripheral to their career aspirations is one of the challenges she faces, but the active-learning strategies she’s employing are helping her teach core competencies like data literacy, observation and hypothesis testing that are relevant to all of the sciences.

“Students coming into biology see it as a facts-and-figures discipline: know all the bones in the body, know how my digestive system works, know how to tell a squirrel from a chipmunk,” Manson said. “They see it as a rote-learning discipline, but it’s not. It’s a problem-based discipline like all other STEM disciplines.”

Adopting active-learning methods is helping change that mindset with her students. She’s also seeing a change in mindset among the faculty.

“One of the valuable things that’s coming out of this is the communication that’s happening across Grounds about the things that are working, sharing strategies and recognizing that we have, in many cases, the same cohort of students going through all of our classes. They’re all facing the same challenges. A student who is having a hard time in biology is probably also having a hard time in chemistry, and it may seem like a simple thing, but we just haven’t had the channels of communication to have those conversations before,” Manson said.

Jim Rolf, director of the lower division courses in the Department of Mathematics, had also been working with Gail Hunger to address the changes that need to happen in the department’s introductory courses to close the learning gaps they were experiencing before he joined the Advance Fellows. One of his department’s unique challenges is that most of its introductory courses are taught by graduate students who only teach for a few years before moving on, and his experience as an Advance Fellow is giving him insights that are helping him address the challenges they face.

“We expect a high degree of pedagogical sophistication from our instructors, and we also expect a high degree of cultural competence, and these are things that take years to develop for most people,” Rolf said.

The instructors are applying an aspect of Columbus and Hunger’s course known as a “growth mindset,” which is based on the idea that learning is a product of trial and error and high-stakes grading early in the course can short-circuit the process.

In practice, Rolf explained, the concept involves giving the students shorter tests more often, which gives the students more opportunities to demonstrate proficiency. It also gives the instructors more opportunities to spot where students are having trouble.

“The goal, Rolf said, is to have high expectations combined with a belief that our students can meet those expectations if we meet them where they are and provide them with appropriate support.”

The department is also focusing on developing a stronger community for their students. If students don’t feel like they belong or that they fit in the course, Rolf said, it affects their learning.

“If you’re teaching students, you have to consider all of who they are. We’re trying to help the whole person move forward,” Rolf said.

Committing the Resources to Succeed

One clear outcome of the work of the Advance Fellows is that efforts to make classrooms more inclusive will require additional support. Investments in classrooms and technology that can accommodate innovative teaching strategies, funding for administrative support and the backing of University leadership are essential ingredients in the continued growth of the coalition’s efforts.

As a first step, the University recently announced that it has received a grant of $529,500 from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, an internationally recognized leader in supporting excellence in STEM discovery and education, through a program it calls Inclusive Excellence 3, or IE3, that will help begin the work of expanding the College’s efforts to advance equity and inclusion in all its introductory STEM courses. The HHMI is also funding a $2.5 million initiative known as Driving Change that aims to enhance the academic experience and success of STEM students, particularly those who belong to historically excluded groups, by facilitating collaboration between the College and UVA's School of Engineering & Applied Science to provide academic support, enhance undergraduate research, and support student success in STEM programs. Arts & Sciences, Engineering and the University will also provide additional funding, bringing the combined total investment to $7.7 million.

The moves will build on the University’s efforts to facilitate communication between its STEM departments, and the College’s participation in the IE3 initiative will connect it to a learning community of 13 other colleges and universities, all committed to shifting from deficit-focused to achievement-oriented thinking and practices through activities like inclusive curricula, student empowerment, inclusive collaboration, and broader approaches to institutional transformation. The College will also launch a formal effort to begin the process of collecting data to evaluate the results of its involvement in IE3 and its impact on students.

The moves will build on the University’s efforts to facilitate communication between its STEM departments, and the College’s participation in the IE3 initiative will connect it to a learning community of 13 other colleges and universities, all committed to shifting from deficit-focused to achievement-oriented thinking and practices through activities like inclusive curricula, student empowerment, inclusive collaboration, and broader approaches to institutional transformation. The College will also launch a formal effort to begin the process of collecting data to evaluate the results of its involvement in IE3 and its impact on students.

Josipa Roksa, associate provost for undergraduate education at UVA and a sociologist who studies higher education with a focus on student success and equity, will play a central part in facilitating the success of the program as IE3 project director at the University. The launch of IE3 at UVA, she said, represents the creation of a learning community and a formal effort to create an unprecedented dialogue across disciplines about how to improve student experiences in introductory STEM courses that are crucial indicators of their success in college and their persistence in their majors.

Data collection efforts will be led by Lindsay Wheeler, assistant director at the Center for Teaching Excellence, and will provide faculty members with clearer insight into what’s working in the classroom and what’s not, and Roksa believes that the University’s involvement in IE3 represents a commitment on the part of the College’s leadership to the importance of the work and a recognition of the challenges it presents.

“There’s a unified voice now that I haven’t heard before,” Roksa said. “From the department chairs to the deans to the provost to the president, there’s a unified voice across the administrative ranks about the significance of this work and about the importance of supporting our students and ensuring that all of them have opportunities to excel in STEM. Working together as a community and having administrative support and recognition will make this initiative a success.”

“This is transformative work,” said Christa Acampora, dean of the College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. “The funding we’ve received from HHMI will accelerate our ability to build on the work that our chemistry faculty have begun and will enhance our capacity to foster similar successes for students in other disciplines and programs. This work is vital for us to help ensure our students will succeed in their chosen fields and for UVA to be a truly great and good public university.”